Preface

Some may wonder why I have chosen to share this story of survival and rescue, especially since the stories of many others impacted by the earthquake did not end well, at least in human terms. I will never pretend to understand why God allowed me to be rescued, and though I celebrate with my family, I do not take lightly the difference between my outcome and the suffering of others. My story is truly a bittersweet one, and I live every day with the loss of those who did not survive that tragic day. I tell my story because I had an encounter with God in the midst of this crisis—my weakness meeting his strength—an encounter that has changed me forever, and one that I believe can bring hope to others. As a painter is drawn to set brush to canvas and a dancer starts to move when he hears music, I feel compelled to give voice to my experiences and testify to the grace of the God who was with me in the depths of my ruin.

It is for this purpose—to glorify God—that I was created, and this is the only reason for this book. I pray that as you face times of adversity, as well as times of abundance, you will also call out to our unshakable God.

Memory is a fickle friend, subject to time, aging brains, external influences, and even the limits of personal perception. Although I have made every attempt to accurately represent my experiences, I recognize my perception and memory were also affected by darkness, strong emotions, and a weakened physical condition. Where I was confused, I have tried to reconcile my understanding of events through the recollections of others who shared these situations. In some cases, I have allowed the confusion I felt to remain in the story so you can experience it with me (with subtle clues to alert you to it), just as I have tried to bring you along into my moments of fear or sadness. And though I did my best to recreate dialogue based on the essence of real conversations, there is no way I could document every word with complete accuracy.

I have made a few alterations to my story intentionally. For privacy reasons, I masked the identity of a few ¬people, including some whom my wife, Christy, talked with, attributing those conversations in this account to different individuals. I also adjusted the spelling of Luckson’s name (to Lukeson) to assist in pronunciation.

Many have asked me what I have learned through these experiences. The answer to that question keeps changing as more time passes. My answer on January 15 was different from what it was in April, which is different again from my answer in July 2010 when I was putting the finishing touches on this book. The lessons learned that I share in the final chapters represent a snapshot in time. Even now, my experiences still feel so new and raw that I expect the lessons I take away will continue to be refined over time. You can join me in this journey of discovery at Earthquake-Survivor.com.

Finally, more than at any time in my life, I have seen how fleeting our time here on earth is. If you find yourself moved by anything you read in this book, please take action. Right now. Don’t let time, or the busyness of life, rob you of your resolve.

Invest yourself fully in those relationships you value most. Get your heart right with God and accept his grace. Perhaps join the fight against poverty and other injustice in the world. Whatever changes you feel called to make in your life, let this story be an effective catalyst to push you to action. Live this day, this moment, this breath, with full purpose and intentionality.

SOLI DEO GLORIA

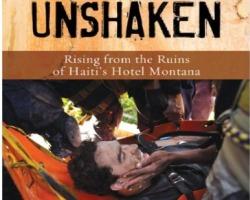

Buried in Haiti

I spit out the blood and dust that coats my mouth, but I can’t spit out the fear. Buried beneath six stories of rubble, the remains of what was once the Hotel Montana, I’m hanging on to the realization that I lived through an earthquake. I survived! But I also know that if I want to make it out of this black tomb alive, if I ever hope to see my family again, it will take a miracle—a series of miracles.

Miracles I’m not sure I have the faith to believe in.

In the complete darkness, I can’t see a thing. The dust in my nose prevents me from smelling anything but concrete. I rub my arms and feel flecks of dust and debris sticking to the hairs. Wiping debris off my face, I can feel a paste where dust mixed with sweat. My body feels weak and broken. The fine powder collects on my eyelids, making them feel heavy. It would be easy to just close my eyes and drift off—to sleep, to death. But one thought keeps me awake and motivated: I have to live so I can get back to my family. How will my wife, Christy, react when she finds out I am buried in Haiti? It turns my stomach to think about her and the boys learning about the quake.

I need a place to rest and think about what to do next, but the elevator floor I’m sitting on is covered in jagged blocks of concrete and debris. I try to extend my legs, but the car is too small for my six-foot frame, and my feet touch the opposite wall. I try to adjust my body so that I am sitting diagonally to give myself room to stretch. I keep my legs spread apart so my knees don’t touch and cause more pain in my leg wound. I had hoped that sitting still would diminish the pain, but with each beat of my heart my leg throbs with intense pain. I adjust my balled-up sock, putting it between my head and the wall to keep pressure on my wound. My thick hair feels sticky and warm to the touch—not a good sign. It means my head is still bleeding.

I’m getting tired, but I’m afraid to fall asleep. What if I slip into unconsciousness? Sleep feels like a significant threat—especially if I have a concussion or drift into shock. Even in the best case, sleep means giving up control of managing my circumstances. I’ve survived an earthquake; I’m not going to die in my sleep. I fumble for my iPhone and set the alarm to go off in twenty minutes. That way, even if I fall asleep, I won’t nap long.

A poem by Dylan Thomas comes to mind. I had read it in college but hadn’t thought of it in years. “Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

That’s what I am going to do. I will rage against anything that might keep me from returning to my family. I take an inventory of my resources: my camera and iPhone, my passport, my journal, and a pen or two. Not much. I wonder if it is even possible to survive. And more importantly, if I don’t, what might happen to my wife, Christy?

Christy had been diagnosed with clinical depression soon after we married. It took nearly six years before we were able to get it under control with therapy and medicine, but since then we’d enjoyed ten years of health and a happy marriage. Yet Christy and I both knew how quickly she could fall back into that black abyss. All it would take was a tragic event, something happening to one of our boys, or the death of one of her parents. With God’s help, we had walked through her sickness together, but one thing we failed to anticipate was that something might happen to me.

Sitting in the darkness, I had to admit—things didn’t look good.

I didn’t sleep. I set my alarm again. And again. And yet again. That gave me the chance to assess my situation every twenty minutes. I wasn’t sure I could hold on until rescuers arrived. Even in the worst disasters in the United States, buildings collapsed one or two at a time, not a whole city at a time. When ¬people are trapped, professional rescuers—police, firefighters, and specially trained search and rescue teams—are on the scene in minutes, hours at most. They have trucks, equipment, extensive training, and experience. They have emergency plans, backup plans, and worst-case scenario plans.

But I wasn’t in the United States.

I was buried in Haiti—one of the poorest countries in the world—and they had nothing. I was trapped in the wreckage of my collapsed hotel in an elevator car the size of a small shower. Despite all of that, I knew I was fortunate to be alive. I suspected that my colleague, David, had died instantly.

In order to survive, every decision I made had life-and-death consequences, but only one had eternal importance. Could I trust God for whatever came next? In the dark, with my head pressed against the elevator wall, I cried. Not for myself, but for Christy and the boys.

What would life be like for them if I died?