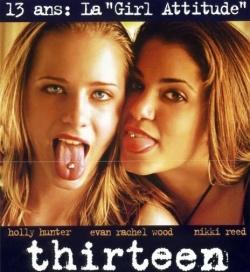

I can’t tell you how many movies I’ve watched through the years in my quest to listen to and better understand the emerging generations. There are a few timeless films that have impacted me so much that I’ve made a habit of watching at least once every year. It’s like having a youth-culture check-up. The Breakfast Club still captures the reality of teen angst almost 30 years after its release. The Dead Poets Society continues to serve as a sobering reminder of how parental pressure undoes young lives. Little Miss Sunshine‘s Duane fuels my compassion for kids struggling with family breakdown and busted dreams. Then there’s the most painful of all these films that I watch each year: Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen, the story of a 13-year-old’s confusing coming-of-age as she searches for significance, purpose and belonging.

When I recently took my annual look at Thirteen, I realized that while youth culture has changed quite a bit in the course of the past decade, the film still speaks to those of us who have long since grown out of our own adolescent years and experience. Thirteen chronicles the struggles of Tracy Freeland as she enters adolescence and morphs from a cute and perky straight-A student into a confused and rebellious teenager looking for her place to belong. At the outset of the film, Tracy turns her back on her life-long neighborhood girlfriends in favor of a connection with the charismatic yet painfully broken Evie Zamor, the most popular and sexy girl in the seventh grade. From there, it all spirals downward as Tracy experiences and responds to a variety of pressures and situations not uncommon to today’s teens. Because of its accurate portrayal of teen reality, viewing Thirteen is similar to having full access to a hidden camera focused on the day-to-day comings and goings of young people.

As Tracy and her generation speak to youth workers, what are they saying to us?

“We’re changing, confused, and vulnerable.”

As Tracy begins seventh grade, it becomes painfully obvious to her and those around her that she is entering a period of earth-shattering change. On the first day of school, she gleefully walks the outside corridors of the middle school campus with her innocent, child-like and life-long neighborhood girlfriends. As they stop to interact with Tracy’s older brother, Mason, and a group of his friends, they notice the boys’ visual and verbal attention shift to Evie Zamora, who has changed from a girl to a woman during summer vacation. Evie’s voluptuous body and seductive dress grab the attention of all as she walks across campus. At that moment, Tracy and her girl-ish looking friends are forgotten as the boys lustily comment on Evie’s transformation. Suddenly, the girls are faced with the fact that they themselves fall far short of Evie on the spectrum of change. While little or nothing is said, Tracy’s expression communicates that she doesn’t have to wonder long about how far along she is in the process. She sees herself as the little girl left behind. On the middle school campus where there are now full-grown women, those who are insecure little girls are trapped in unhappiness. So, Tracy’s battle with herself and everything in her world commences as she resolves to push ahead and forcibly move herself into adulthood as quickly as possible.

In a poignant scene symbolizing the confusing transformation from child to adult, she responds to being looked down on as a child by Evie and her friends. Tracy gets home from school and angrily empties her bedroom of her cherished stuffed animals and little girl toys and decides to grow up. She angrily goes so far as to throw them—and other things representative of her childhood—into the trash. She then proceeds to trash her life-long friends, dropping them so she can pursue a friendship with Evie.

The moments of Tracy’s life shared with us in the remainder of the film serve as poignant reminders of the uncertainty, storms and stress faced by teenagers who not only have to experience the normal developmental changes associated with the adolescent years (physical, social, emotional, intellectual, moral), but they have to do so in a culture where social pressures are on the rise and many of the social supports that should guide young people through these years have collapsed or disappeared altogether.

The door of childhood is closing on Tracy’s life. The doorway into adolescence is opening wide, and she’s not sure what she sees or where to go. For Tracy and many of her friends, the teenage years are all about survival and finding their way. Consequently, they are susceptible to any person, institution or entity that has the intended or unintended power to define and shape who they are. In a word, the emerging generations are vulnerable.

“Our support systems aren’t working and it’s stressing us out.”

In Tracy’s case, the foundational institution of the family has been broken by divorce. Dad is conspicuously absent. When he does appear, Tracy’s longings for a connection with her father are shattered again as their planned weekend visit is cancelled because he has business responsibilities, and their short face-to-face conversation is interrupted by his attachment to his ringing cell phone. Tracy lives with her mom, Mel, a recovering alcoholic struggling to make ends meet for her family. Mel attempts to meet her own relational needs by opening her home and bed to an on-again off-again boyfriend who is a recovering cocaine addict. While Mel’s attempts to provide for and guide her two children are valiant, her efforts are frustrated by the reality that what she is trying to hold together has been terribly broken by past choices and present circumstances. Tracy has no support.

Like so many other teens from broken homes, the vulnerable young Tracy—already dealing with the normal pressures and challenges of adolescence—seeks support, refuge and identity with a peer. Sadly, Evie’s situation is markedly worse. Her father and mother are totally out of the picture. Abuse is part of her past. Currently, she lives with a guardian whose own life, not surprisingly, is a train wreck. In Evie, Tracy finds a support system that never has had a support system herself. Again, a confused child is led by a confused child in a difficult and confusing adult world.

The reality of living in today’s society has made Tracy and her peers more vulnerable to stress while exposing them to stresses and situations almost unknown to previous generations. Interestingly, the church and its ambassadors are conspicuously absent from Tracy, Evie and Mel’s stories. The only positive and caring adult presence is a teacher who challenges Tracy on the sudden decline in the quality of her schoolwork.

“We need a place to belong.”

Teenagers enter adolescence feeling insecure and unsure of themselves. They desire to fit in and belong. If they don’t, they see themselves as abnormal.

Consequently, pursuing and adopting the image of those who are accepted, desirable and interesting can become a consuming passion dictating appearance and behavior.

Very quickly, Tracy’s quest for belonging takes her to a new peer group, specifically Evie, the envy of the seventh grade class who appears to be mature beyond her years and seems to have everything together. Without knowing Tracy is in pursuit and hoping for a first encounter, Evie heads to the restroom. Tracy catches up, and their chance meeting turns out to be everything Tracy hoped for. Instead of rejecting Tracy’s advances, Evie invites Tracy to go shopping later that day. As Evie disappears into the girls’ room, Tracy dances with ecstatic joy. She’s made a connection! In her mind, she’s on her way to belonging. Suddenly, feelings of significance surge through her being. From that point on, Tracy’s relationship with Evie begins, and her newfound place of belonging is actually the start of a downward spiral that takes Tracy to the brink of self-destruction. Still, in the adolescent mind, it’s a small price to pay for acceptance.

The price of Tracy’s acceptance and belonging winds up being exceptionally costly. In no time at all, Tracy engages in theft, shoplifting, drug abuse, illicit sexual activity, lying, use of profanity, a radical change in appearance, and a variety of other distressing behaviors. Tracy’s unmet need for belonging is an invitation for outside socializing factors to take the place of a strong home, to move into her life, and then to shape who she already is, as well as what she is becoming. Tracy was suffering the consequences of her choices and the fallout from her lack of belonging.

“We’re hurting, and hurting deeply.”

From the moment Tracy makes the decision to connect with Evie, her already fragile and confusing young life takes a turn for the worse. Together, they embark on a series of dangerous and risky behaviors. They have become in Dean Borgman’s words, troubled youth, that is, “young people in imminent danger of inflicting serious injury on themselves or others.”

As the movie unfolds, viewers are treated to a host of disturbing and sometimes graphic portrayals of the pain Tracy feels as the result of her decisions. Her cries are not always verbal and direct. At times, they are silent. Her obsession about body image leads to eating issues, a problem so widespread in today’s youth culture that it is an epidemic. She engages in risky and immoral sexual behaviors from performing oral sex on a classmate, to engaging in a passionate practice kiss with Evie, to willing participation in group sexual activity as she and Evie team up to seduce an older male neighbor in his living room. She experiments with drugs and alcohol. At one point, she and Evie—both giddy and high from huffing—willingly exchange face punches in an effort to feel something other than their emotional numbness. The punching is so severe that it leaves them bloodied. Perhaps the most alarming manifestation of Tracy’s growing emotional agony is her attempt at self-therapy through self-mutilation. On three occasions during the film, she slices her arms in an effort to release her emotional burdens. Tracy and her peers are hurting, and hurting deeply.

“Will you be here for us?”

As Thirteen comes to a close, the film’s final three scenes send a loud and clear message to our adult culture and to youth workers. The first scene is emotionally riveting and telling. Tracy’s mother, desperate to do something to help her daughter, takes a big first step in the right direction. At a moment when Tracy is exhibiting her extreme frustration and confusion in a fit of rage, Mel refuses to walk away. Instead, she grabs her daughter, pulls her in close though she is putting up a fight, and squeezes her in a way that says, “I am here, and I will not let you go.” For a moment, Tracy resists though her mother is offering something she’s hoped for. Eventually, her resistance stops and she collapses into her mother’s arms while both weep.

Next, the camera focuses on the two as they lay together sleeping in Tracy’s bed. Tracy is backed into her mother’s body. Lost in her mother’s embrace, their hands are entwined and Tracy feels a safety and peace she has not experienced for quite some time. Her mother is there for her.

In the third and final scene, viewers are reminded that while Tracy has experienced far more than any human being—let alone a 13-year-old—should have to experience in terms of brokenness, agony and pain, she is still just a little girl. The camera captures Tracy’s face as she spins on a piece of playground apparatus, then the picture of youthful innocence is shattered by reality as the little girl who is playing lets out a blood-curdling scream. Just like that, the film ends.

What will we do?

Thirteen unmistakably testifies to the universal longing of fallen humanity—especially the emerging generations—for spiritual wholeness and restoration. It continues to issue marching orders to those of doing youth ministry. We must understand kids better than they understand themselves. Our churches must be places where they can belong. We must offer hope and healing to meet their deep hurt. We must be present in their lives.