A chain of elephants, trunks and tails linked, wanders, with a mixture of upbeat energy and complacent pride, along the endpapers of a children’s book.

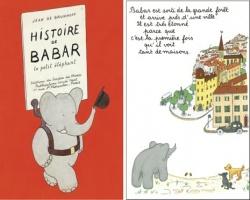

So begins one of the stories that most please the imagination of the modern child and his distant relation the modern adult–Jean de Brunhoff’s The Story of Babar, published in 1931. The Babar books are among those half-dozen picture books that seem to fix not just a character but a whole way of being, even a civilization. An elephant, lost in the city, does not trumpet with rage but rides a department-store elevator up and down, until gently discouraged by the elevator boy. A Haussmann-style city rises in the middle of the barbarian jungle. Once seen, Babar the Frenchified elephant is not forgotten.

With Bemelmans’s Madeline and Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, the Babar books have become part of the common language of childhood, the library of the early mind. There are few parents who haven’t tried them and few small children who don’t like them.