We model irresponsible financial habits within our youth ministry, then wonder why our students are so affected by consumerism. Practical alternatives aren’t as hard as you think. In fact, they can be kind of fun.

When the topic turns to sex or violence, we youth leaders are a pretty outspoken bunch. Our bookshelves and lesson files are loaded with material aimed at counteracting the blitzkrieg of destructive messages our students receive on these subjects in film, television, music and magazines.

It’s a strange battle. Our objective is clear: to teach students the importance of sexual abstinence and Christian love. Yet we fight the battle as if the entertainment industry had the opposite objective: to promote teenage sex and violence. But few writers, musicians, filmmakers and network executives have such a sinister goal in mind. Their objective is simply to make money. Sex and violence sell.

It’s no wonder that the entertainment industry has conquered youth culture. While we’re preoccupied with reinforcing our students’ moral defenses, they’re attacking on economic ground. And we’ve left that field undefended. Except for the occasional sermon on giving, most youth leaders spend little time teaching students real money values. What’s worse, many of us model irresponsible money habits in our households and ministries.

Until we get serious about passing on wise and godly money values to our students, we will be fighting a lopsided battle for their moral health. Maybe it’s time to offer an alternative to the frenzied consumerism they see each day.

1. Rethink the Debt Thing

Lots of parents actually encourage their kids to go into debt. They figure that the pressure of making regular monthly payments for a car will teach responsibility and prepare teenagers for adulthood.

This idea of responsibility through indebtedness should be called Safe Debt. The message: Debt is unavoidable, so at least carry a cosigner.

There are many other methods for teaching responsibility. Students who support a child through a sponsorship program learn it. So do those who tithe their income or time to ministry or who work all year to pay for their summer mission trip. There are dozens of ways for students to demonstrate responsibility: stay in school, don’t have sex, drive sober, stick by your friends, stand up for God. Next to these, car payments teach nothing.

Debt’s great allure is that it permits us to have stuff now instead of having to wait until we can afford it. But there’s something not quite right about this principle. The person who goes into debt to buy “stuff” is like the absent award nominee who prerecords her acceptance speech, or the engaged couple who goes ahead with intercourse, or the person who sins because he knows God will forgive him. Each is collecting the prize before the race is won.

It’s likely that most of your students’ families are in debt with car payments and credit cards. It’s also likely that the children will model the parents. They need an alternative model. Get rid of your debts. Pay cash for a used car—your students will trash it anyway. Reserve your credit line for the day God calls you to minister in the city or overseas; you may need it to cover the shortfall in support.

If you need further encouragement, stand in front of your students and confess that their wise and responsible youth leader keeps his savings in a bank account paying 5 percent interest, then borrows it back from the bank on a credit card that charges him 18 percent.

2. Stop the Stockpile

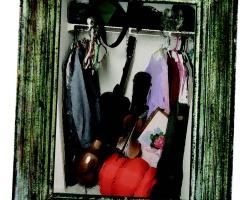

As kids, we didn’t worry about stockpiling our possessions; we grew out of clothes and broke toys faster than our parents could buy new ones, so closet space was generally available. Well, we’ve stopped growing (vertically, anyway) and we’re a little gentler on our toys now that we pay for them ourselves, so our closets are filling up with new stuff. But we’re not unloading the old; we’re stockpiling.

If your world is filling up with stuff, establish a non-accumulation policy: Whenever you want to get something new, you have to get rid of something like it. If you want a new shirt, you go to your closet and pick out a shirt to give away. A pair of new shoes costs one pair of old shoes, given to Goodwill. Birthdays and Christmas can be tough because you may get lots of clothes as gifts and have to give away as many items.

The biggest payoff with a non-accumulation policy isn’t what it does to your storage space but how it changes your values. Your buying habits will change—getting a new toy will not only cost you money, it’ll cost you an old toy you like as much. It also compels you to attach the act of giving to the act of receiving. If you want something, you must give something. There’s a gospel message in here somewhere: if you try it, you can turn it into a talk.

3. Quit Offering Paid Vacations

Lots of youth mission trips are merely sightseeing vacations in disguise. We bill them as mission trips simply because it’s easier to raise money for a jaunt through Europe when we slip in a couple of days of church-building in southern France (the country that somehow managed to build Notre Dame and the Eiffel Tower without us).

Almost any cross-cultural experience will have a positive effect on a student; a trip to Europe will rearrange the way your students think about the world and their places in it. But if it’s not a full-blown mission trip, don’t say that it is just to loosen purse strings.

Save your fund-raising efforts for true missions. The next time a student comes to you for help in writing a fund-raising letter for a vacation-in-disguise, help her write a job résumé instead.

4. Lighten Up on Subsidies

Many churches subsidize the cost of youth retreats, camps, concerts, and special events to make these activities more affordable to their students. It’s a great idea—indeed, many students would be excluded from significant ministry experiences without such assistance. But when the church chips in $20 so that a healthy, middle-class, cash-rich kid (wearing a $100 pair of shoes) can go on a $40 retreat, something is wrong.

Subsidies can also mess up your students’ perceptions of value. For example, students know that most live concert tickets cost $10 to $50. So when you subsidize their $10 Christian concert ticket down to $5, they may figure that Christian music is half as good as “real” music or that the church is just rich and can afford to pay people to attend.

In the real world, if your product is too expensive for your customers, you cut costs and lower your price—or convince your customers that your product is worth the higher price or find new customers or go out of business. If most of your students can’t afford an activity, you have the same choices:

A. Choose a more affordable activity.

B. Convince them that this activity is worth more than whatever else they spend money on.

C. Start a ministry to rich kids.

D. Choose a new career.

You see the problem already. Most of us choose option B; but when our last-minute marketing blitz fails to muster the minimum in sign-ups, we cancel the activity, eat the camp deposit or the concert tickets and start pondering option D.

Next time, pick an affordable activity, charge the real price, and make sure the program is worth every dollar. Save your subsidies for the few who really need them.

5. Unload Excess Stuff

The first time you moved away from your parents’ home, you didn’t own much. Maybe you packed a suitcase or two with clothing and filled a few cardboard boxes with trophies, photo Albums, and your music collection.

Your next move was tougher—you had to borrow a friend’s pickup to carry everything, including those nifty shelves you made from boards and bricks, plus the junk your roommate left behind when he moved out in the middle of the night without paying rent. A few moves and several roommates later, you’re renting a U-Haul truck and bribing strong-backed friends with pizza and promises you’ll return the favor on their next move.

Now you’ve reached the point where they won’t rent you a truck big enough to move all your stuff because you’re not licensed to drive a semi. So you hire a moving company. As you’re boxing up your 53rd carton of possessions, you ask yourself, Do I really need to own all this stuff?

Part of you is saying there’s nothing wrong with owning so many things—they make life easier and more enjoyable. But another part of you (including your lower back), questions whether you might be happier with less: less clutter, fewer headaches, lower costs for fixing and mending (something is always breaking) and less worry about stuff being stolen.

Here’s an idea: Get rid of it. Not all of it—just the stuff for which you really can’t think of a compelling reason to hold on to. Go through the closets and cabinets, shelves and cupboards, looking for anything that isn’t essential. With each suspect item, ask yourself this question:

Would my life be worse off without it?

If the answer is no, put it in a “pass it on” pile. Now pack it up and pass it on to the Salvation Army. (Safety tip: If you’re married, make sure your spouse has a chance to veto your decisions—or you may find yourself at the thrift store, buying back your own possessions.)

When you’ve cleaned house, tell your students about the experience and encourage them to do the same. Then get a smaller home to fill with your reduced possessions and call for a discount in your insurance because there’s less to burn, bash and burgle. In fact, now you can have the junior high group over for a lock-in.