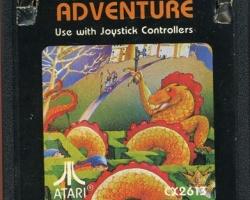

If any game designer enjoys eternal security in video game history, it must be Warren Robinett. Taking his inspiration from Don Woods and Willy Crowther’s text-based game “Adventure,” Robinett labored for six months to redesign that game as the image-based “Atari Adventure.” In so doing, he ushered in a new genre that directly paved the way for landmark series such as “Ultima,” “The Legend of Zelda” and “World of Warcraft.”

In 1979, “Adventure” introduced the gaming experience of a persistent, expansive and fully navigable off-screen world, populated by creatures with lives and personalities of their own. Although this world encompassed 30 screens, the player—represented by an on-screen cursor—could see and explore only one screen at a time. Restlessly searching for the elusive Enchanted Chalice, the player traversed far and wide through a series of castles, labyrinths, catacombs and dungeons.

Along the way, the player alternately hunted and fled from a family of three strangely duck-like dragons named Yorgle, Grundle and Rhindle. The kingdom also hid a handy assortment of magical items—an arrow-shaped sword, a u-shaped magnet, a large purple bridge and three castle keys. However, the player could carry only one item at a time. In order to unlock a castle drawbridge, the player had to leave the sword behind in order to fetch the key from a remote location. Making matters worse, a chaotic bat tended to swoop in to steal away a useful item or drop off a dragon at the most inopportune time. No video-game player had ever before conceived of anything so mythical and magical as “Adventure.”

Perhaps “Adventure”‘s most enduring story is the tale of the mysterious “Easter Egg” phenomenon. Receiving an annual salary of $22,000, Robinett single-handedly designed and coded the “Adventure” cartridge for the original Atari VCS. “Adventure” went on to sell a million copies at $25 each. However, Atari refused to pay Robinett one penny of royalties for his contribution.

Adding insult to injury, Atari also refused to give Robinett any credit for his work on the box art or game manual. All of this was company policy. Thus, Robinett was moved to sneak an undocumented secret room into his game world. Within that secret room, a marquee read, “Created by Warren Robinett.” Only the cleverest players would ever find the hidden “Grey Dot” that unlocked the entrance to this secret message.

For its day, myth and magic infused Robinett’s “Adventure” with an almost transcendent sense of mystery, awe and wonder. Players spent dozens—or hundreds—of hours mapping terrain, plumbing the depths of its lamp-lit dungeons, searching for hidden rooms, testing the properties of each magical item and poring over the secrets of the kingdom. “Adventure” was a timer-less game, as well, allowing for welcome moments of careful contemplation and reflection.

The transcendence of “Adventure” also was experienced within the “non-Euclidean structure” of its pathways, as Mark Wolf suggested in The Meaning of the Video Game. Screens that seemed to connect east and west also connected north and south, inexplicably. Although walls and borders constrained player movement, the dragons and bat broke those rules through their own form of “god movement.” Their special powers enabled them to phase through all walls and borders in order to pounce on the player at any moment.

Perhaps the most wondrous of all “Adventure” experiences occurred after the player’s death. Once eaten, the player sat in the dragon’s belly until the bat swooped in, picked up the dragon and flew around the kingdom on a carefree tour that afforded a bird’s eye view otherwise inaccessible. Playing “Adventure” was an immersive encounter with anticipation, imagination, nervousness, dread and delight.

Likewise, the life of faith is a transcendent journey into mystery, awe and wonder. In the midst of an increasingly mechanized and modern world, we need enchantment more than ever before. We too often try to turn the faith journey into something that we master and, in so doing, fail to honor its essential nature as something that masters us.

This journey is less a technical problem to be solved than a transcendent potentiality to be savored. To paraphrase that great mythmaker, C.S. Lewis, transcendence is a faith-enriching gift that “stirs and troubles” us “with the dim sense of something beyond our reach and, far from dulling or emptying the actual world, gives it a new dimension of depth.”