In his excellent book, Hurt: Inside the World of Today’s Teenagers, Chap Clark reminds us the most basic task of adolescence is individuation, the journey of becoming an individual, the odyssey of becoming one’s own person. He describes it as a quest in search of authentic answers to four basic life questions:

(1) “Who am I” (the quest for identity);

(2) “Where am I going with my life?” (the quest for autonomy or purpose);

(3) “How do I—or how should I—relate to other people?” (the question of intimacy);

(4) “How do I know these things, and how can I know that I know?” (the question of epistemology).

If we’ve been in youth ministry more than 20 minutes and taken the time to listen to students and to the culture in which they live, we can appreciate this fourth and final question as the most important of all. Because how our students answer that fourth question—”How do we know that we know?”—will determine how they’ll pursue their search for an answers to the other three questions. How ironic that, for our students, their search for life begins with the very same question by which Pilate concluded Jesus’ sentence of death: “What is truth?” (John 18:38).

In the past 10 years, there has been important, robust discussion about the question of truth in a postmodern context. Books were written, forums were convened, wagons were circled, heads were shaved, soul-patches were grown; and it became almost impossible to go to a youth convention without someone raising what felt to be (at least to some people) profound questions about the nature of truth. Rightly so. How can we help our students answer the huge questions that stir their hearts and souls if we cannot answer this most basic question: How do we know, and how do we know what we know?

I, for one, am satisfied with neither modernism’s nor postmodernism’s answer to this question. I think both approaches lead us down the wrong road, although in opposite directions. Unfortunately, in an article such as this one, it isn’t possible to explain or critique either position adequately. (For further thinking on both sides of the coin, see the brief bibliography at the end of the article.)

I’d like us to consider a third approach that will take us beyond modernism and postmodernism. If we really wanted to be edgy and hip, we could call it “post- postmodernism.” The philosopher Charles Pierce called it “critical realism.”

Critical Realism and the Kids in Your Youth Group

For a culture such as our own, critical realism might offer the sort of framework in which our kids can begin to answer the all-important question: “What is truth?” It may be worth our attention.

Here’s a quick explanation using the familiar Umpire Metaphor: The modernist umpire says, “There’s balls and there’s strikes, and I call them the way they are.” This position, sometimes called naive realism, assumes there really is something called a strike zone, and it is possible for the umpire to be absolutely objective in his appraisal of every pitch with respect to that zone. This is the umpire saying, “Personal interpretation has nothing to do with it. I can know absolute truth about every pitch.”

The postmodernist umpire says, “There’s balls and there’s strikes, but they ain’t nuthn’ ’til I call ’em.” With this position, the umpire is saying, “Look, who are we kidding? The very concept of strike and ball is a cultural construct, and those terms have no real meaning apart from a particular game played in a particular place. What one guy sees as a strike another guy sees as a ball. There are no absolutes.”

The critical realist umpire says, “There’s balls and there’s strikes, and I call ’em the way I see ’em.” This umpire is telling us something quite different from the postmodernist. He is telling us, “The rule book is absolutely clear about what are and are not balls and strikes, and they are what they are regardless of what I think. That doesn’t mean I always get the call right, but we are not left with uncertainty. There are clear absolutes, and my calls can be objectively measured by the standard of that rule book.”

I think this third approach to truth is not only the one that most closely reflects the biblical perspective, but also offers authentic hope to our kids who are awash in a storm of uncertainty. Here’s why:

1. Critical realism addresses the basic presupposition that truth is a matter of perspective. One of the most basic premises of postmodernism is that truth is perspectival /per-speck-tiv-al/; it is a matter of perspective. Clearly, it is a premise of postmodernism that our culture and our kids have swallowed hook, line and sinker. That is why, when you finished your Bible study on premarital sex last week, several students came up at the end to say, “I understand what you said tonight may be true for you, but can you be tolerant enough to understand it isn’t true for me?” That is why we had youth ministry book titles such as, Youth Specialties’ Stories of Emergence: Moving from Absolute to Authentic (note the subtitle).

Critical realists agree perspective is certainly a factor in how we see reality. To use Leonard Sweet’s phrase, “None of us can claim immaculate perception.” Because of that, modernism’s promise of objective truth is presumptuous. Science claims more than it can deliver, whether it is delivering evidence that God doesn’t exist or evidence that He does. Critical realists go on to say that while perception impacts how we view reality, it does not create a reality. Reality is what it is, regardless of how we see it. Balls are balls, strikes are strikes, and they are defined absolutely in the baseball rule book. Every single pitch is authentically a ball or a strike regardless of what the umpire says. Truth is not solely a matter of perspective.

2. Critical realism takes seriously the challenge of using language to communicate truth. Postmodernists argue that truth is a matter of perspective because truth claims are expressed in language. The problem is that language is made up of words, and words are subject to our interpretation—interpretations that are very much affected by everything from family background to heritage to history to culture. What we see and hear is based on what we’ve seen and heard.

That is why in a Bible study, students are less likely to say, “What does it say?” and more likely to say, “This is what it means to me.” Most of our students are too young to remember their president testifying under oath that he didn’t really commit perjury and break the law because “it depends on what the meaning of the word is is…” However, they have come to accept that every statement or truth is subject to interpretation. Postmodernists argue to an extent that there are no absolutes.

The problem is that postmodernists make these claims as if they are absolute, which is a little ironic. They make them with words, as if we know what these words mean. If words have no true meaning, then every sentence is nonsense—even the sentence that proclaims, “Words have no true meaning,” which is why critical realists would argue that at some point postmodernism becomes little more than a parlor game. That was the point C.S. Lewis was making when he wrote (The Abolition of Man): “…you cannot go on ‘explaining away’ forever. You will find that you have explained explanation itself away. You cannot go on ‘seeing through’ things forever. The whole point of seeing through something is to see something through it. It is good the whole window should be transparent, because the street or garden beyond it is opaque. How if you saw through the garden too?…If you see through everything, then everything is transparent. But a wholly transparent world is an invisible world. To ‘see through’ all things is the same as not to see at all.”

Once you’ve argued that language has no meaning, it’s a little tough to get dialogue going.

3. Critical realism helps us understand we don’t need to leave behind absolute to get to authentic. Critical realism affirms that when we use words to represent reality, whether terms such as ball and strike or rebirth, heaven, hell and Trinity, they do represent reality; and by represent we do not mean the formal or literal one-to-one correspondence of photographs. Instead, critical realism tells us to think of knowledge as a model, a map, a blueprint of reality. We can know truth absolutely, but in a certain way.

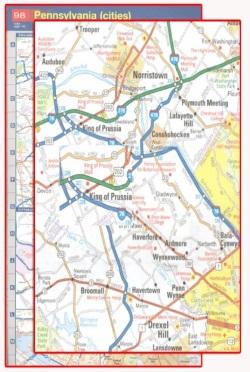

For example, here is a map of King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. I live near there in a little area called Valley Forge.

This map communicates absolute truth, but only in a certain way. In the first place, the correspondence between the map and reality is symbolic. If you were ever to visit the King of Prussia area, you would see the roads and highways in that area are not actually different colors, and there are no town names scrawled across the countryside.

This map is not a photograph of reality. It is a model, a mental diagram, similar to an analogy. It conveys limited but accurate information about reality. You have to understand it that way or you might say the cartographer is not giving us an authentic picture.

For example, in the blow-up map of the King of Prussia area, you might be able to find a small square located between three major highways. It’s labeled “King of Prussia Mall.” It’s large, and my wife likes to shop there. They have a Chick-fil-A there. However, it is not a perfect square as the map seems to indicate; and if the picture were in color, you would see the square is red. That’s not actually accurate either. The King of Prussia Mall is not a red square (That’s actually in Moscow.) So the map communicates absolute truth authentically, but only in a certain way.

4. Critical realism helps us to understand we do not need absolute knowledge to have absolute truth. Because words are like maps, they have real meaning and can represent absolute reality. They can guide us with absolute certainty without communicating absolute knowledge. In fact, a map such as the one you see on this page is more helpful because it doesn’t provide absolute knowledge. Map-makers have to be selective. We don’t reject a road map because it has failed to include a notation of every bend and bridge. The truthfulness of a map is not measured by the accuracy of its extraneous information but by the information it claims to present truthfully.

This is important because our students (and even some of us as youth workers) have inherited a sub-Christian humility about the truth claims of Christianity. It can be characterized by the following statements, each of which is valid to some extent:

A. “I believe Christianity is true, but I do not believe my version (or yours, for that matter) of the faith is completely true.” (In other words, I believe that all versions are incomplete in some ways, weighed down with extra baggage, and marred by impurities, biases, misconceptions and gaps.)

B. “I believe Jesus is true, but I don’t believe Christianity in any of our versions is true. (In other words, we know in part and prophesy in part; we have not yet reached that unity and maturity of faith and knowledge that will come when we know as we are known.)

C. “I believe there is no completely true version of Christianity anywhere except, of course, in the mind of God. (In other words, incompleteness and error are part of the reality of being human” (McLaren, The Church on the Other Side, p. 172-173).

What is invalid in these statements is the notion that because we do not have absolute knowledge, we need to be timid about absolute truth. The Scripture says we see but “a poor reflection as in a mirror” (1 Cor. 13:10); it does not suggest we cannot see at all. It certainly doesn’t seem to be saying we should claim to be blind. We need not be squeamish about what we know. If someone wants to get to the mall, and he or she is lost, it makes little difference to that person whether the road crosses the stream here or there as long as someone can indicate a road on the map that gets the person to the intended destination. Absolute knowledge is not what we need to help them. What we need is absolute certainty, absolute truth.

5. Critical realism reminds us truth matters. For a map to be helpful, it must have positive analogies—there must be a direct correspondence with reality. In other words, if we go to the intersection of Routes 76, 202 and 276, there better be a mall near there. Otherwise, the map has no value. The truth of the map is measured not by whether most people understand or agree with it, but by whether it reflects reality. There really is a King of Prussia Mall. So, we must ask: Is it really where the map said it would be?

It is clear this approach to truth reflects the view of the apostles. Paul takes great pains to explain in 1 Corinthians 15 that the resurrection is not just a matter of opinion or perspective. He is talking about this as a truth claim that represents reality. It really happened. Contrary to the postmodern notion that we create our own realities, there is no sense in which the New Testament writers seemed to believe they were creating the story. No, they were reporting it; and their testimony would rise or fall on whether their reports matched the real events, times, places and characters.

Our Students Need to Know They Can Know They Know

Our students are yearning for certainties in a world that seems only to offer questions. How we frame the truth claims of the Christian faith is a matter of supreme importance. Because I know some of my postmodern friends share my sense of urgency and concern for these kids, I can trust only that we will continue this dialogue. I hope so. We can’t afford to be just doers. We must be thinkers..and only fools build on a shaky foundation.

For Further Reading:

• Postmodernizing the Faith: Evangelical Responses to the Challenge of Postmodernism, Millard Erickson (Baker Books): Provides a spectrum of six ways—three negative and three positive—for thinking about postmodernism from the perspective of an evangelical;

• A Generous Orthodoxy: Why I Am a Missional, Evangelical, Post/Protestant, Liberal/Conservative, Mystical/Poetic, Biblical, Charismatic/Contemplative, Fundamentalist/Calvinist, Anabaptist/Anglican, Methodist, Catholic, Green, Incarnational, Depressed-yet-Hopeful, Emergent, Unfinished CHRISTIAN, Brian McLaren (Zondervan): Provides an engaging and well-written explanation of how a postmodern mind-set enhances our understanding of faith;

• Becoming Conversant with the Emergent Church: Understanding a Movement and Its Implications, D.A. Carson: Provides a thorough critique of postmodernism and the emergent movement, specifically the writings of Brian McClaren;

• This Way to Youth Ministry: An Introduction to the Adventure, Duffy Robbins (Zondervan): One of the chapters on culture includes my own more thorough effort to assess the ideas behind, and the strengths and weaknesses of the postmodern framework.