This article originally appeared in print journal May/June 2001.

Thanks to February’s Grammy Awards hoopla, thousands of Americans are now finally aware that all those young people talking excitedly about Eminem haven’t been referring to the sugar-coated chocolate candy called M&Ms.

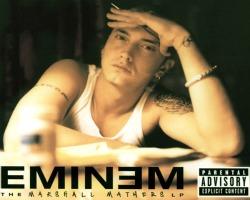

There’s nothing sweet about Eminem, a 28-year-old white rapper whose violence-obsessed, profanity-laced albums have generated soul-searching debates about the coarsening of popular culture while selling multiple millions of copies.

If you haven’t yet given a listen to Eminem’s The Marshall Mathers LP, which won the Rap Album Grammy, borrow a copy from one of your kids and listen to track one, “Public Service Announcement 2000.”

In less than sixty seconds, a speaker informs listeners that Eminem doesn’t give a **** what they think of his music, that they can **** his ****, that merely purchasing the album means they have already kissed his ***, and that Eminem is fed up with their **** and might even kill them if they don’t shut up.

Morally, things go downhill from there. The rest of the album explores incest, bestiality, murdering prostitutes, killing girlfriends, attacking gays, and much, much more.

Two years ago, this column discussed the interesting fact that it has been white, adolescent suburban kids who make up one of the biggest audiences for rap music, a genre dominated by black artists until the arrival of Eminem (who happens to be produced by black rap veteran Dr. Dre).

Now, Eminem has declared color irrelevant. “I don’t do black music,” he says on one cut. “I don’t do white music. I do fight music for high school kids.”

And in a bold declaration found on the cut “The Real Slim Shady,” which won a Grammy for Rap Solo Performance, Eminem says he speaks for an entire generation of kids:

“There’s a million of us just like me, who cuss like me, who just don’t give a **** like me, who dress like me, walk, talk and act like me.”

At a time when some parents worry about the mixed messages their kids are hearing on CDs by the precocious Britney Spears, the music of Eminem represents a troubling message from the pit of adolescent hell.

And by the way, we should probably mention here that technically speaking, Eminem’s albums are musical masterpieces. The melodies are catchy, the beats are compelling, the raps are fast and furious, and the production is nothing less than stunning.

In fact, few pop culture products in recent history have confronted consumers with such a stark contrast between technique and content.

On the surface, The Marshall Mathers LP is a powerful testimony to the creativity that God has lavished on all his creatures. But not far underneath that glossy surface is the reality of humanity’s desperate lostness, and maybe even the decadence of an entire culture.

In short, regardless of what one makes of his music, it seems safe to say that Eminem is a truly gifted—but possibly deeply twisted—musical genius.

He is also a musical chameleon.

From cut to cut, Eminem moves from persona to persona. On some tracks he’s Slim Shady, a dark and immoral character introduced on his 1999 album.

In “Stan,” which, thanks to constant play on MTV is one of the album’s biggest hits, Eminem raps out the role of Slim, a rap artist who has become the focus for an obsessed fan named Stan.

In the song, Stan (played by rapper Dido) writes a series of letters to Slim, none of which are answered until it’s too late. “I can relate to what you’re saying in your songs,” says Stan in a final, desperate cassette tape he records for Slim during the process of throwing his girlfriend into the trunk of his car and driving off a bridge to his death.

On other tracks Eminem plays Marshall Mathers, which is his legal name (M & M). On the cut “Marshall Mathers,” Eminem raps out the part of a young man who has sold millions of albums. Bathed in the warm glow of celebrity, he suddenly finds that people who once ignored him now seek his blessing. (As he raps on the cut: “Nobody ever gave a **** before; all they did was doubt me”).

On “The Real Slim Shady,” Eminem calls out, “Will the real Slim Shady stand up?” By this time, the listener is probably wondering the same thing.

If it all sounds a bit confusing, it is. In fact, Eminem’s work may be the perfect soundtrack for a postmodern age in which no only the notion of truth but even the very concept of a fixed identity has been deconstructed to nothingness.

Of course, pop artists have been playing with personas and adopting various roles for decades. Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson was “Aqualung,” a demented street person. Ozzy Osbourne made a career of playing a Satanist, a role that has recently been revived by “Antichrist Superstar” Marilyn Manson. Alice Cooper, now a Christian, started out playing a woman in a man’s body before moving on to assorted other roles.

But Eminem takes role-playing to dizzying new levels, leaving listeners—particularly younger listeners—wondering who he is and what he stands for. Lyrics about hating gays, which gained criticism from various gay groups, were apparently just a front; because Eminem performed a duet on “Stan” with openly gay musical legend Elton John.

Some people predicted that Eminem would win the Grammy for best album, but he didn’t. That honor went to Steely Dan, whose acclaimed comeback album, Two Against Nature, was their first new release in 20 years.

That album featured songs like “Cousin Dupree,” a catchy song about a man who has an incestuous crush on a much younger cousin. But critics didn’t raise a stink about “Cousin Dupree” or some of Steely Dan’s other songs about depravity, in part because their album is intended for balding baby boomers. Eminem’s albums, on the other hand, are targeted at teens and pre-teens. And it doesn’t take a developmental psychologist to tell you that such youngsters may have difficulty distinguishing between an artist like Eminem and his various musical personalities.

Is the character who knocks off women in “Kill You” (track two) the same person who stars in “Drug Ballad” (track 13)? It’s impossible to tell. And are teens who listen to songs like these experiencing vicarious thrills by allowing Eminem to help them walk on the wild side? Or are they merely tuning in to an ongoing drama series, much like watching successive installments of The X-Files?

Frankly, nobody knows what your kids are making of Eminem until somebody asks them. But one thing’s for sure, they probably knew who he was and were probably aware of some of his music long before the Grammys.

All kinds of gross and disgusting things can grow in the darkness. But God makes it his business to expose darkness to the light. You can do the same thing with some of the kids in your group.

It may not be the best approach to confront them by putting them and their musical choices in the blinding brightness of a spotlight where all can see and criticize. Rather for some kids, particularly those who most deeply identify with Eminem’s lyrics, it will take friendship, support, love and encouragement to enable them to reveal their musical secrets and the unexpressed inner feelings that the music helps them articulate.

I don’t like what Eminem is saying, and there are many in the musical community who don’t think the Grammys should have honored his work. Still, his music is there and it clearly speaks to millions of kids.

But we will never know exactly what it says to them until we ask them.