This article first appeared in print journal May/June 1998.

It’s not every day that moviegoers hear the sounds of Steven Curtis Chapman’s “I Will Not Go Quietly” coming from a theater’s loudspeakers—or the Bill Gaither Vocal Band doing “There Is a River,” or Russ Taff singing “Ain’t No Grave,” or Gary Chapman and Wynonna dueting “I’ll Fly Away.”

Or Lyle Lovett leaning into “I’m a Soldier,” Johnny Cash crooning “In the Garden,” Sounds of Blackness belting out “Victory Is Mine,” and Emmylou Harris performing “I Love to Tell the Story” with Oscar-winning actor Robert Duvall.

“Is this a movie theater,” some may ask, “or a revival service?”

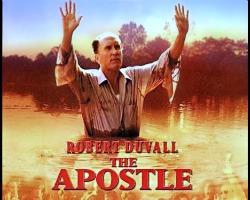

Almost. The music appears on the soundtrack to Duvall’s critically acclaimed film The Apostle. Released to the Christian market by Sparrow Records, The Apostle Soundtrack: A Revival for the Soul isn’t just Hollywood hype.

The CD’s title is an apt description for this musical collection—as well as for Duvall’s film about a flawed but faithful Pentecostal preacher.

“It’s all in a day’s work,” says the veteran of nearly 60 films (his first was 1962’s To Kill a Mockingbird), including such storied projects as The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, Lonesome Dove, The Great Santini, and Phenomenon.

But Duvall has a soft spot for films about faith. He won his Oscar for a touching portrayal of born-again country singer Mac Sledge in Bruce Beresford’s 1983 version of Horton Foote’s Tender Mercies.

The Apostle—which Duvall researched, wrote, directed, and financed—opened in January, earning Duvall another Oscar nomination (he lost out to Jack Nicholson) for his moving portrayal of a southern Pentecostal evangelist’s gradual fall and ultimate redemption. During a phone interview from his Virginia home, Duvall said making the film was like a divine mission.

“It’s something I had to do,” he says. “I think in a way it could be a calling, but it’s hard to judge in absolutes what that all means.”

The son of a Methodist father and a Christian Scientist mother, Duvall inherited a deep respect for “the writings of Jesus Christ, the importance of his niche in this world, and the fact that you gotta practice what you teach.”

Today many of those beliefs still hold. “I believe in one God, and I’m a Christian. But I have an individual outlook. It’s a private thing.”

With The Apostle, Duvall’s reverence for Christian teaching and his attraction to southern Pentecostal preaching—which he calls “one of the true American art forms”—have produced a piece of unique and historic cinema. Finally Hollywood’s cameras lavish the same kind of respectful attention on a Bible-thumping evangelist that Hollywood usually gives to gun-toting gangsters and stiletto-wielding serial killers.

“We make great gangster movies, so why not make this kind of movie right, too?” asks Duvall, who invested $5 million of his own savings to make The Apostle after numerous studios turned him down.

“This is something I’ve had in the back of my mind for years,” he says. “I wanted to do something that I’ve never seen done without caricaturing these people or patronizing them. I wanted to give them their due and their respect.”

Hucksters and hypocrites

American moviemakers created two glowing portrayals of Tibetan Buddhism last year—Seven Years in Tibet (Brad Pitt as mountaineer Heinrich Harrer) and Kundun (Martin Scorcese’s affectionate portrait of the Dalai Lama). But The Apostle may be the first warm, positive—and honest—portrayal of a Pentecostal evangelist in American film history.

What took so long?

“Hollywood,” Duvall says quietly, “doesn’t understand the subject matter.” A brief survey of four decades worth of movies about preachers is proof enough.

Elmer Gantry (1960) is the classic of the genre. Based on the 1927 Sinclair Lewis novel, this big-budget film teams a Billy Sunday-like con man and an Aimee Semple McPherson-like female evangelist for a damning look at the religion racket. Burt Lancaster won one of the film’s three Oscars for his over-the-top title role.

In a rare move, the film’s creators didn’t want to rely solely on the on-screen action to make their point, beginning the movie with the following disclaimer:

We believe that certain aspects of Revivalism can bear examination—that the conduct of some revivalists makes a mockery of the traditional beliefs and practices of organized Christianity!

We believe that everyone has a right to worship according to his conscience, but Freedom of Religion is not license to abuse the faith of the people!

Decades later, it was Leap of Faith (1992) that revealed a revivalist’s hypocrisy. Steve Martin wasn’t very convincing as traveling evangelist/scam artist Jonas Nightengale, but his technique of receiving divine “revelations” about revivalgoers’ lives, troubles, and medical conditions from an assistant (Debra Winger) and a hidden earpiece was copied directly from real-life religious con man Peter Popoff, who was exposed by hoax buster James “The Amazing” Randi.

Marjoe (1972), which won an Oscar for Best Feature Documentary, shows how former child evangelist Marjoe Gortner could still frisk the flock even after he’d lost his faith. The Disappearance of Aimee (1976) rises above its made-for-TV origins in reenacting McPherson’s controversial 1926 absence, which she claimed was an abduction—and others ascribed to hanky panky.

Real sin, real grace

The amazing thing about The Apostle isn’t that it gives an accurate portrayal of sin—which is something all these other films do quite well. Duvall’s character, Euliss “Sonny” Dewey—a sincere man who preaches the Bible and saves white, black, and souls of other hues with a consuming zeal—is also a womanizer.

(Not so unusual. About 37 percent of pastors responding to a 1991 Fuller Institute of Church Growth survey admitted to participating in inappropriate sexual behavior with a church member of the opposite sex.)

No, what’s amazing about The Apostle is its moving portrayal of the reality of grace—something that’s much more difficult to pull off. Sonny does have a weakness for women, but his lusts don’t invalidate his deep devotion to God.

Duvall’s hard work researching Pentecostals and other people of faith shows up in numerous scenes based on real-life experiences. When Sonny preaches to a dying man injured in a car wreck, for example, Duvall is just recounting the actions of a woman evangelist he knows. When sonny confronts a troublemaker played by Billy Bob Thornton, convincing him to accept Christ instead of bulldozing his church, Duvall is simply choreographing an event a friend of his experienced.

In addition to professional actors, the film features true believers who’ve never starred in anything bigger than the church Christmas pageant. Their zeal brings life to the film’s many realistic worship scenes.

Duvall says he isn’t trying to preach in The Apostle, but he is trying to reach two distinct audiences: Mainstream moviegoers who’ve never seen the power of Pentecostalism—and Christians who’ve only been treated to religious films that Duvall considers “very corny…melodramatic movies.”

And like the soundtrack, which succeeds in bringing together an impressively diverse group of musicians, the movie succeeds in building bridges between hardcore Christians and the unchurched—all of whom are transfixed by the film’s slow-burning action.

New York Times writer Janet Maslin calls The Apostle “a rare display of spiritual light on screen,” while a reviewer for the conservative Christian Movieguide writes: “There is much to be said in favor of this movie, but most significant is its positive affirmation of God, church, and evangelism.”

If you’re tired of corny religious movies and want to see a film that mixes grit and grace in equal measure, check out The Apostle. And make sure you allow plenty of time to discuss it with your friends (or youth group).